Academic requirements

You are expected to work independently in defining the problem and backed by your academic knowledge to argue for its relevance. You will also be expected to supplement your academic knowledge with additional literature and to show that you are able to choose relevant methods in your attempt to answer your problem.

What are the requirements to your paper

It is important that you know the requirements and the objectives for the paper you are about to write. In your curriculum you can read the description of objectives, assessment criteria and which academic skills you are expected to acquire on all the courses of your programme.

If you are in doubt about the requirements to your papers, you are always welcome to ask your study supervisor or lecturer.

In the introduction you must give a short presentation of your research area. You must also clearly outline the premises of your paper, in order for the reader to see its professional relevance. You may choose to refer to (a) major theoretician(s) to show that you are writing in a professional context.

It may also be relevant to mention what you choose not to research in your paper. Keep in mind, that you are writing to someone who knows more about the research area than you do. Consequently, your text must reflect that it’s a professional text by using relevant, professional concepts.

Here is an example of an introduction:

| |

| I would like to write a paper on young adults, noise and hearing impairment. There is focus on noise in the work places because it is generally recognized that working for hours in a room with a lot of noise, heightens the risk of permanent hearing impairment. But when e.g. going to a discotheque, you also expose yourself to a lot of noise with the risk of a hearing impairment. Why do they do it? Don’t young adults know that it may damage your hearing? Or is something making them ignore the risk? |

It is vital, that your problem definition opens up to a paper which is investigative/analyzing and not descriptive. The reader must experience concrete learning from the paper. A problem definition may go like this:

The reader should know that…….

This shows the reader that your paper will display an actual processing of knowledge, and that it will answer a concrete question.

If the paper starts like this: The reader should know something about…..

This opens up to a paper in which you are conveying knowledge not processing it, and that is not the objective.

An example of a problem definition:

| |

| I’d like to do research into whether young adults know that being in environments where they are exposed to loud music may result in hearing impairment. And why they voluntarily expose themselves to a potentially harmful acoustic impact. |

The importance of method varies depending on your programme. But generally, the method serves to help the reader see and evaluate what you do and how you do it.

This may be the part where you describe your findings in the literature you have drawn on in your paper. You may e.g. list which databases you have used to reach your result. You must supplement your knowledge with the literature presenting the latest results/findings in your research area.

An empirical project

If you’re doing an empirical paper where you need to compile the empirical data yourself, the paper must include parts that deal with e.g. the methodology in connection with using quantitative or qualitative interviews. This part is of a more general character which serves to show that you have a critical approach to data collection. If you compile the data yourself through e.g. qualitative interviews, you need only few respondents. You don’t have time and do not have experience in processing large collections of data. Naturally, interviewing 5 persons is not representative, but methodically it is of no importance, because it is the same techniques and considerations that lie behind a study where you interview 5000 persons.

An example of important questions to answer in the methodical part:

| |

| How do I decide how many persons to interview? How do I find them? How can I interview them in a scientific way? And what do I always need to pay attention to about when compiling data? |

At this point you present the reader with your theoretical knowledge. You will be assessed on your ability to systematize complex knowledge, and you may e.g. do that here where you in a short, precise and appropriate way describe a theory on a limited number of pages. Focus on whether the theoretical knowledge you present is relevant for your paper.

An example of how to divide your theory:

| |

| Here is a section about 1) music and the brain, 2) hearing and hearing impairment 3) Sound levels in discotheques 4) underlying psycho-social causes for exposing oneself to something potentially harmful/damaging. |

Here you present your research area. It may be any number of things, but it may be e.g. a poem, a novel, a short story, a political speech, an historical document, a marketing strategy, a study...

An example of important questions to answer in connection with your research area:

| |

| My compilation of data: Who did I ask? How did I choose the respondents? What questions did I ask? And why? What challenges did I experience while compiling the data? |

At this point, you must compare your research area with the professional knowledge you already have. You must let your observations correspond with the theories, and you may point out if there is disagreement on how to interpret your findings.

It is very important that you do not let our sources say more than they actually do. If you have interviewed 5 young persons you may, of course, not generalize about all young people.

An example of the contents in a discussion and an analysis:

| |

| How does what young adults say about noise in discotheques compare to the theory? Maybe they don’t think it’s so harmful? Or are they not counting on that it may affect them? Which theoretical explanations are there as to why young adults continue to expose themselves to noise, and does the literature support it? |

This is where you answer your problem definition, and it is very important that you do not answer more than you have set out to do. It does not have to be new and pioneering research, but you have proved your findings by means of transparent, scientific methods.

An example of a conclusion:

| |

| Now the reader knows that young adults generally are aware that it is risky to expose themselves to noise, but still do it! |

A perspective may be directly applicable or may point in the direction of new research areas.

An example of a perspectivation:

| |

| Now I have knowledge about young adults' attitude when it comes to exposing themselves to loud music. What prophylactic activities could be established? And, if so, who should establish them? |

The bibliography is the complete list of all the sources you have drawn on in your paper. There are various standards for how to present it. You must ask your supervisors, how they prefer it and follow their directions to a tee. It is also part of your identity as an academic that you are able to draw up a correct bibliography.

Focus on how to apply your knowledge

When writing a major paper you are expected to demonstrate your ability to apply knowledge. Your research question must be precise, and you’ll especially be tested on how you reach your conclusion. Major papers especially serve for you to be able to demonstrate your academic and intellectual skills.

Levels of knowledge

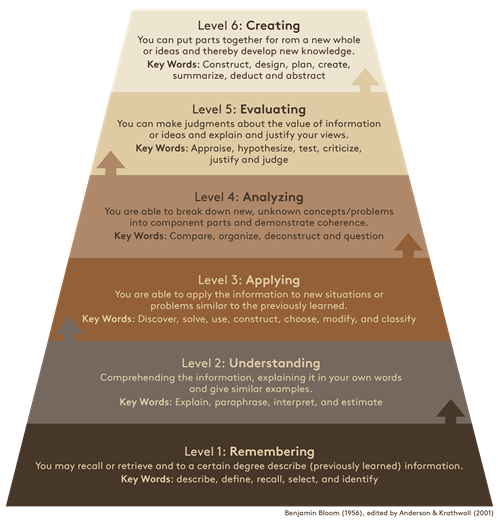

Benjamin Bloom, the American psychologist, has developed a taxonomy of learning domains. The taxonomy’s levels move from the known to the unknown and at the same time from the simple to the complex. It illustrates that knowledge should be regarded as existing on various levels and that you need to focus on how to apply knowledge and not only to have knowledge. The learning goals in the curricula correspond to levels 3, 4 and 5 in the taxonomy.

(Click on the chart below for larger version).